One of my favourite lines in TLaC is when Doug Lemov states: “The complete sentence is the battering ram that knocks down the door to college.” Insisting pupils answer questions or contribute to class discussions in full sentences will support them to write in full, well-articulated sentences. Put simply: if they can say it, they can write it.

I sometimes roll my eyes when I hear appeals to developing pupils’ ‘oracy’, as it can be one of those generic, positive-sounding catch-alls that sounds great and would be hard to argue against, but can also mean whatever the person saying it and the person hearing it want it to mean, which can be something great, or nothing much at all. But, of course, the genius of TLaC is its focus on the specific and the concrete, and Format Matters is a brilliantly simple, implementable way to develop ‘oracy’ in the service of making pupils cleverer.

However, this is not easy to embed in classrooms, as reflected in this honest and insightful blog by Yousuf Hamid (@yousufhamid), an economics teacher in London: https://mydiminishingreturns.blogspot.com/2021/05/the-benefits-of-making-pupils-respond.html. Yousuf identifies several familiar barriers to doing this effectively, from explaining to pupils why it is important, through simply remembering to insist upon it and overcoming the sense that it is somewhat ‘cringey’ to do so, to persisting when pupils find it hard.

I have been drawing on the recent excellent ‘The Power of By…’ blog by Adam Boxer (@adamboxer1) to be more precise in the action steps I set for my trainees by (see what I’m doing here…) using the ‘Achieve X by…’ formulation: https://achemicalorthodoxy.wordpress.com/2021/04/27/the-power-of-by/.

I recently had cause to give feedback on this very aspect of classroom practice and so I thought it would be useful to outline how I did so, using Adam’s ‘Power of By…’ to hopefully overcome some of the barriers identified by Yousuf.

Here is my feedback, with actions steps phrased using the ‘Power of By…’:

Breaking them down to explain one by one:

- Communicating to them that they should answer verbally in full sentences before they begin a discussion task and/or before you pose questions;

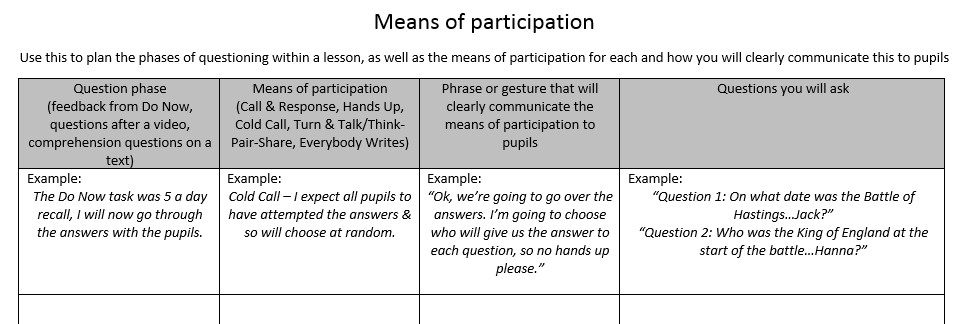

Including the expectation in your communication of the Means of Participation is crucial. Firstly, it is an opportunity to reinforce the expectation. Secondly, it gives pupils the chance to rehearse their answers in the format you require during the discussion task, which makes it more likely they will be able to produce a full sentence response out loud to the class.

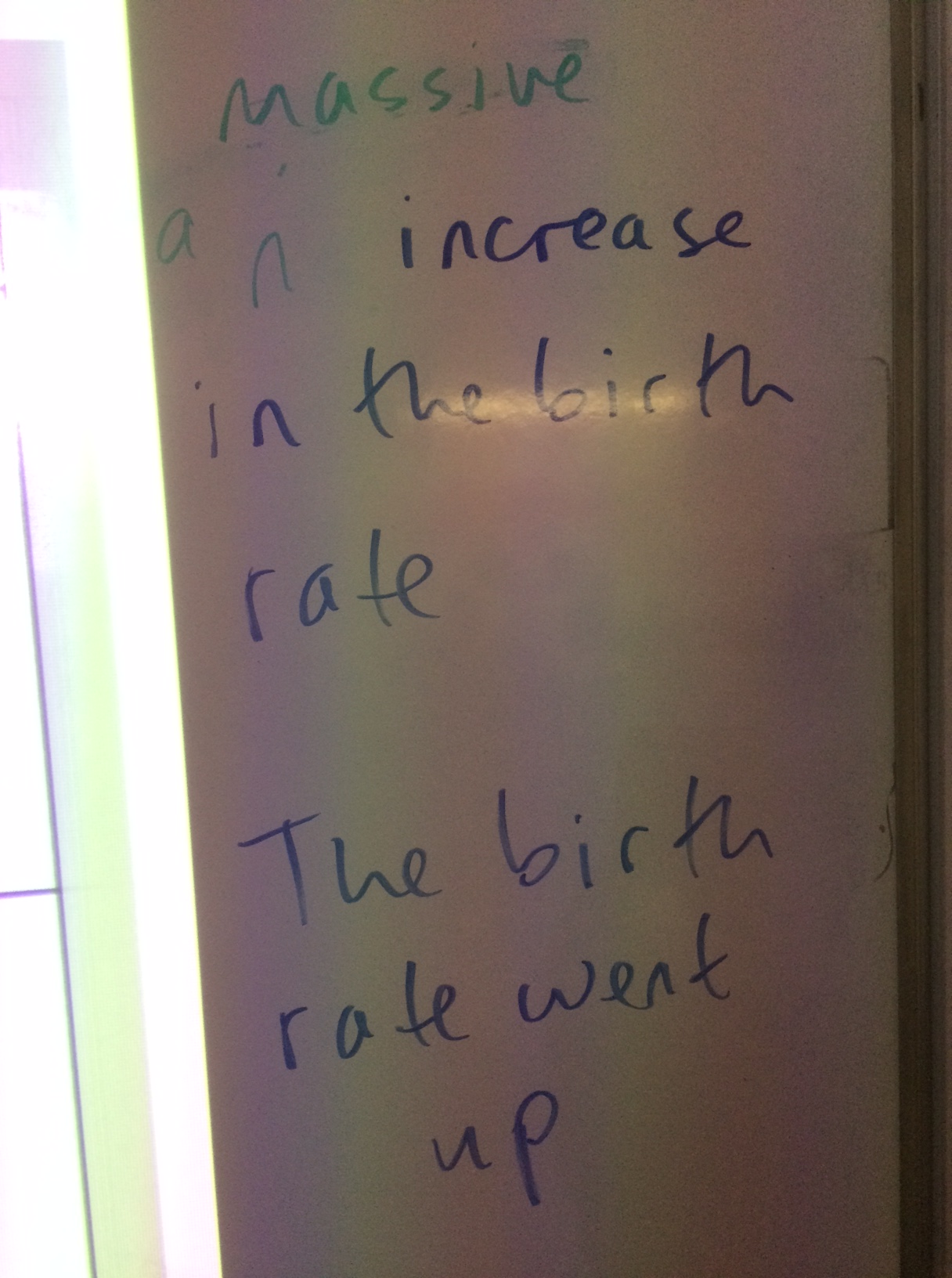

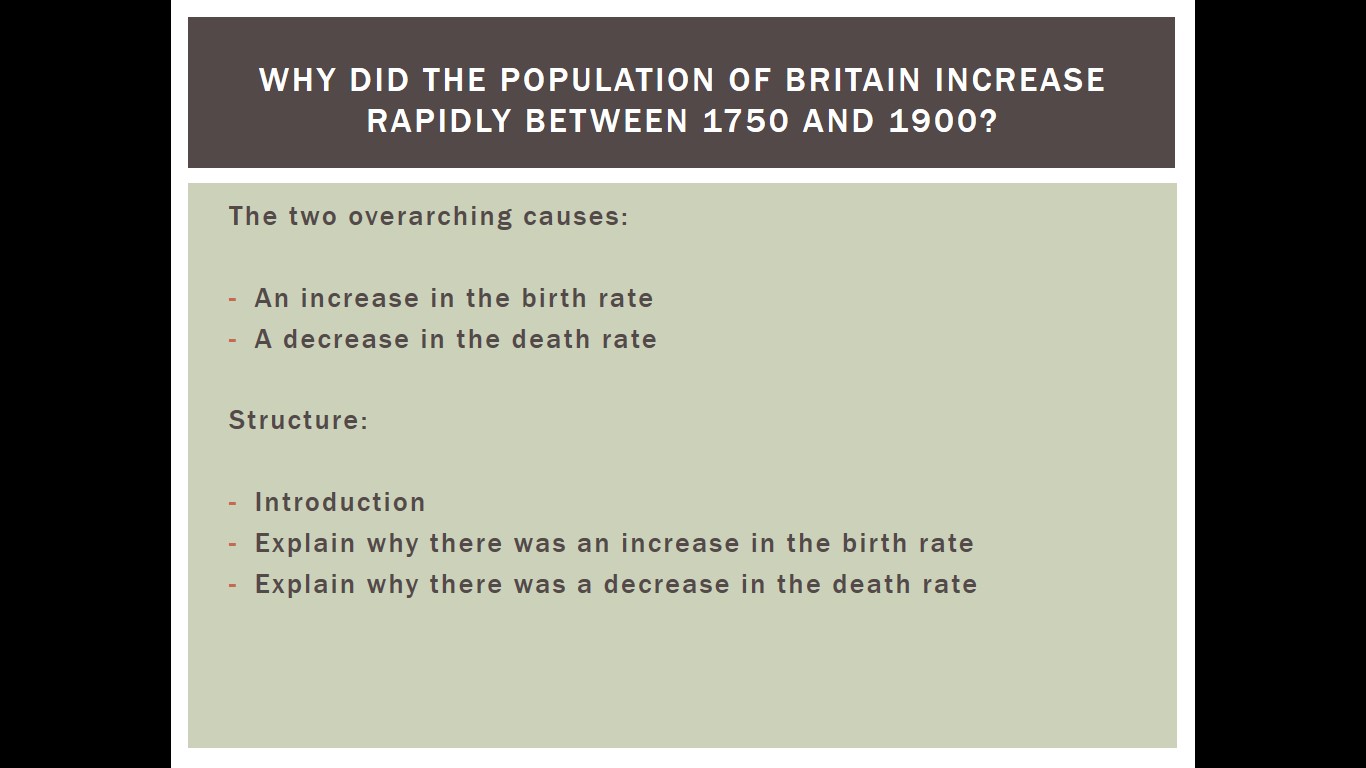

- Using the writing frames/sentence starters you plan for their writing as ‘speaking frames’, by directing pupils to these to structure their answers.

Especially when you first introduce this expectation, pupils will find it hard both to remember and to do. We are used to using sentence starters and writing frames to support writing, so using the very same structures a ‘speaking frames’ will support pupils when the expectation is new to them.

Alternatively, a prompt such as ‘use the wording of the question and turn it into the start of your answer’ can help, eg:

Question: “In which year was the Battle of Hastings fought?”

Answer: The Battle of Hastings was fought in…”

Again, direct pupils to these before their discussion/before you pose the question, so that they can rehearse.

Now we get into what to do when pupils don’t answer in a full sentence. There are probably three reasons for this: they forgot to, they don’t want to, or they can’t. I think we should respond by tackling the reasons in that order, in a kind of Least Invasive Intervention but for verbal answers. Doing so increases the level of support incrementally, reserving the possibility of giving the pupil more support to meet your expectation each time, but without jumping straight to the maximum amount of support and thus needlessly compromising Think Ratio for the pupil. It eliminates the barriers to full sentence answers incrementally, moving from tackling ‘hasn’t’ to ‘won’t’ to ‘can’t. Our first response should therefore assume the pupil has simply forgotten the expectation:

- Not accepting fragments of sentences as answers, and where pupils answer in fragments, repeating the expectation: “In a full sentence please”;

This is hard, especially if the pupil has answered ‘correctly’ (“1066, Sir.”), or you know that the particular pupil who answered may find it difficult to answer in full sentences. However, a simple reminder, followed by a pause to give the pupil thinking time, may yield a self-correction and the required full sentence answer.

However, if the pupil still doesn’t meet the expectation, the next step is to assume they can, but are refusing to:

- If a pupil still does not answer in a full sentence, referring them back to the ‘speaking frame’ and giving them time to reformulate their answer;

If a pupil can but doesn’t answer in a full sentence, then referring them back to the given speaking frame, or the tip about using the question to phrase the answer, removes their ability to pretend they can’t. Again, allowing a pause while they use the prompt to formulate their answer should hopefully yield the full sentence answer that is expected.

If still no full sentence answer is forthcoming, we move on to assuming the pupils can’t answer thus. Clearly, distinguishing between won’t and can’t is hard: we can’t see inside pupils’ heads. As you get to know a class your ability to judge which of these two applies will increase. In addition, over time, as you insist on the pupils meeting your expectation of full sentence answers, you should be increasingly confident that when pupils don’t meet it it is because they can’t, rather than won’t.

So, lastly:

- When a pupil is still unable to answer in a full sentence, putting their answer into a full sentence for them and asking them to repeat it back to you, as many times as it takes for them to be able to repeat it fluently.

(As an interim step you could repeat the sentence stem for them and ask them to complete it, then ask them to put it together into a full sentence themselves)

If it is still can’t and not won’t then this removes any reason no to at all, and if a pupil still doesn’t then it becomes an issue of defiance, which can be dealt with as a potential behaviour issue.

However, if it is a genuine case of can’t then this final step also removes any barrier to the pupil meeting your expectation, with the hope that as pupils become accustomed both to the expectation, and to successfully meeting it, they are able to do so increasingly independently over time.

The principle of getting the pupil to repeat the answer as many times as it takes to be able to do so fluently is an important nuance here, too. Clearly this is a matter of judgement – if a pupil is really unconfident, or really struggles to articulate themselves then building up slowly will be necessary. However, the more we can give pupils the opportunity to practise, the better. If they never do articulate themselves in full sentences, they will never learn to do so. Ensuring there is a supportive, non-judgemental culture in the class is key here.